ALGONKIN AND HURON OCCUPATION OF

THE OTTAWA VALLEY

(originalement publié en 1909, The Ottawa Naturalist, Vol. XXIII, No. 4: 61-68 & Vol. XXIII, No. 5:92-104)

By T. W. Edwin Sowter

To the student of Indian archaeology, the great highway of the Ottawa will always be a subject of absorbing interest. As yet, it is almost a virgin field of inquiry, as f ar as any systematic effort has been made to exploit it. As yet, there are vast stores of information, along this old waterway, which await the magic touch of scientific investigation, to be turned into romance chapters of Canadian history. Sooner, or later, we must appreciate these potential opportunities for the collection of data that may solve many important ethnic problems, which have been transmitted to us from the dim twilight of prehistoric times and are, as yet, only presented to us in the will-o'-the-wispish light of tradition. The Ottawa River may yet furnish us with clues to the elucidation of much that is problematical in regard to areas of occupation, migrations and dispersions of some of our great native races, who were leading actors in many of the tragic wilderness dramas, that were played out in Canada before and after European contact.

The early Jesuit missionaries have left us, in their Relations a priceless record of Algonkin and Huron sociology, as well as an invaluable basis for the study of such of the Indian tribes of Canada as came within the sphere of their activities. As those gentle and lovable pioneers of the Cross were among the first Europeans to come in contact with these red children of the forest, they enjoyed exceptional opportunities for observing their habits of thought and action, ere their primitive folk-lore and traditions had been modified by the cradle stories of the pale-faces.

We are told by Parkman, one of the most trustworthy historians of modern times, that "By far the most close and accurate observers of Indian superstition were the French and Italian Jesuits of the first half of the seventeenth century. Their

page 61

page 62

opportunities were unrivalled; and they used them in a spirit of faithful inquiry, accumulating facts, and leaving theory to their successors." It is for this reason that the Jesuit Relations should be regarded as the groundwork of Indian archaeology, as far as Canada is concerned. They were written by men of absolute integrity, who have given us as much of the life history of the individual, the clan and the tribe, as came under their observation; or as they were able to obtain from the most trustworthy sources. They describe the Indian, as they found him, embowered in the seclusion of his native forests; surrounded by innumerable okies or manitous, both benevolent and maligant, to whom he appealed for aid in the hour of his need, or propitiated with sacrifices; venerating, with a sentiment akin to worship, such animal ancestors as happened to be the prototypes of his various clans; adhering to mythologies that agreed well in essentials though somewhat loosely defined in matters of detail; believing, in his Nature-worship, in the soul or spirit of the lake, the river and the cataract; but without any vestige of belief in that personification of beneficence called "The Great Spirit" who was presented to him afterwards by the missionaries, as the archetype of mankind, and recommended to him as the Supreme Being whom he should worship.

That the Jesuit record has been dictated by a spirit of truthfulness, is apparent from its impartial treatment of Indian tradition and worship; for, while some writers have endeavored to interpret Indian mythology in such a manner as to make it conforrn to the bias of preconceived theories, these worthy apostles of the Cross have given us the simple truth without embellishments. Examples of this kind may be found in Ragueneau's Relation, of 1648, in which he refers to the Hurons "as having received from their ancestors no knowledge of God; and in the denial of Allouez, in his Relation of 1667, that any such knowledge existed among the tribes of Lake Superior. It is not probable that these men would have failed to recognize any such belief had the case been otherwise. Thus, these subtle reasoners, and past-masters in theological disquisition, were unable to discover, in such manitous as Manabozho, or the Great White Hare of the Algonkins, or, in Rawen Niyoh, the great oki of the Huron-Iroquois, beings analogous to the white man's God.

Now, the writer is convinced that this field of archaeological inquiry should be entered, with the assistance of the "open se-same" of the historical record; and that, by following up the clues, transmitted to us by the Jesuits and other contemporary writers, we should devote our attention to such portions of this field as are most likely to yield the best results, under careful and methodical cultivation.

page 62

page 63

The great stream, which forms the main boundary between the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, was called in early times the River of the Ottawas; but, it might have been named, also,theRiverof the Hurons. Owing to its geographical position, it offered the advantages of a direct and convenient highway between the French settlements on the St. Lawrence and the Indian tribes of the Great Lakes. This river, especially in the seventeenth century, was traversed bv Algonkins and Hurons, Frenchmen and priests, following, either along its shores or at its distant terminals, their varied pursuits of explorers, fur-traders, scalp-hunters or ministers of the gospel. Sometimes, huge fleets of canoes, bearing red embassies from the west, or white punitive expeditions from the east, consignments of furs to the St. Lawrence trading posts, or native supplies for the winter hunt, black robed Jesuits with donnés or artisans for their western missions, passed up or down this great highway; while, at other times, fugitive parties, both white and red, crept along the shadow of its shores to avoid some scalping-party of the ubiquitous and dreaded Iroquois.

We are thus indebted to historical testimony for much of our knowledge of what took place on the Ottawa, since the beginning of the French régime. We should now endeavour to amplify this knowledge, by the accumulation of such data as may be derived from the domain of archaeology. The prospects in this direction, though somewhat dubious at first sight, are much improved on closer acquaintance.

It is no great tax upon our ingenuity to discover traces of the presence of French and Indians on the Ottawa, in bygone times. The Indian dictum that,"water leaves no trail," applies, only to the deeper parts of the stream; for the writer, has in his collection, stone tomahawks of native manufacture, together with trade bullets, which were taken from the shallow shore-water of this river. It is, however, in the ancient camping grounds, which dot the shores of the Ottawa at frequent intervals, that we should search for traces of early human occupation. As the recovery of the loose leaves, which have been lost out of some old story book, is necessary to complete the tale; so is the interpretation of the sign language of these camp-sites, a requisite for the recovery of many lost or unwritten pages of our historical manuscript.

Great care should be taken in the examination of these places. The ground should be all gone over on the hands and knees, as, with his nose to the ground, so to speak, one is not liable to overlook anything of importance. As he is about to turn up a chapter on the social and domestic life of a native community, he should observe the topographical features of the

page 63

page 64

site and the position it occupies relative to the main river, whether situated on its margin or at any considerable distance away from its shores; and also, its proximity to smaller streams that might have been navigated by canoes before the deforestation of the district . He should first of all examine the surface before disturbing it; after which he may search out, the secrets concealed in the ashes of dead camp fires, by passing the ashes through a sieve, so as to retain such works of art as might, otherwise, pass unnoticed. Every work of art, or portion thereof, should be studied with great care, even to apparently insignificant fragments. The composition of pottery should be noted and efforts made to discover if its ingredients are obtainable in the vicinity. All forms of arrow-heads should be noted, as well as the color and character of the flint, or other material, from which they have been fabricated, and, if possible, the source from which this material has been derived should be ascertained. Arrow-heads, that appear to be of foreign make, as differing from the prevailing. forms, should be noted for future reference and comparison. Search should also be made amidst the usual litter of the flint workshops, in the locality, for evidences of domestic manufacture, such as pieces of raw material, flakings of heads that have been spoilt in the making and discarded by the ancient workmen. This flint refuse is found in greatest

abundance about the bases of large boulders, which appear to have been utilized by the prehistoric artificers, as convenient work-benches in their primitive industries. Articles of European workmanship, which are too apt to be considered as of little consequence, should be searched for with the greatest diligence, making due allowance of course, for the difference in relative values between such finds as the rude pistol flint of the ancient hunter, and the metal cap or stopper from the pocket pistol of the well equipped modern fisherman. A sharp lookout should also be kept for implements of slate, especially such as are fabricated from the Huronian variety; and, as a last but most important recommendation, the location of the camp site should be kept a secret from relic hunters, until its examination has been completed.

C.C. James, in his Downfall of the Huron Nation, says that "The history and downfall of the Hurons may be studied in three sources. 1st. The traditions of the Indians themselves. 2nd. The letters of the Jesuit Fathers, the written records commonly called The Jesuit Relations. 3rd. Modern archaeological research and ethnological investigation. These three contributers to a common story are widely different in method, and when they verify one another we are bound to accept the conclusions as facts of history." It may be said also that the

page 64

page 65

same sources of information are available in studying the question of Algonkin and Huron occupation of the Ottawa Valley. We have already considered the value of the Jesuit writings, let us now examine some of the traditions of the Indians themselves.

Life on the old Ottawa, during the greater part of the seventeenth century, was always strenuous and frequently dangerous. On this rugged old trade route, during the french régime, the fur-traders from the interior, both white and red, experienced many vicissitudes while conveying the products of the chase to the trading posts on the St. Lawrence. Shadowy traditions of those days of racial attrition, have been transmitted from father to son, from the old coureurs de bois and their Indian confreres, to their half-breed descendants of the present day. These traditions account for the human bones washed out some years ago at the foot of the old Indian portage at the Chats, and those that are scattered in great profusion at Big Sand Point, lower down the river; also, for quite a number of brass kettles found at one time near the mouth of Constance Creek, for the Indian burials on Aylmer Island, as well as for the presence of arrow-heads, stone celts, flint knives and other native implements in the gravel beds at the foot of the Chaudière, and,without pausing to consider whether these relics of a departed people are not the ordinary litter of Indian camp-sites, or the disinterred bones from Indian burial places, tradition, as usual, takes charge of them as the ominous tokens of a period of violence.

At Big Sand Point there is a sand mound or hillock, fringed with scrubby trees, which has the uncanny reputation of having been once the home of a family of Wendigoes. These Wendigoes, as is usual with this species of manitou, were a source of constant annoyance to the native dwellers on the shores of Lake Deschênes but more particularly to an Algonkin camp on Sand Bay, quite close to the headquarters of these malignant spirits.The old man, who possessed the gigantic proportions of his class, was frequently seen wading about in the waters of the bay, when on foraging expeditions after Indian children of whose flesh, it is said, he and his family were particularly fond. The family consisted of the father, the mother and one son. The bravest Indian warriors had, on several occasions, ambushed and shot at the old man and woman without injuring either of them, but, by means of sorcery, they succeeded in kidnapping the boy, when his parents were away from home. Holding the young hopeful as a hostage, they managed to dictate terms to his father and mother and finally got rid of the whole family.

The writer heard this story one night while camping at the Chats and, though far from believing than any sane Indian of the old school would have laid violent hands on even a young

page 65

page 66

Wendigo, he is quite satisfied that had one of those legendery monsters of the American wilderness loomed suddenly out of the dark shadows of the forest and approached the camp fire, the poor half-breed, who was "spinning the yarn" would have immediately taken to his canoe and left the Wendigo in undisputed possession of the island.

As it is around this same sand mound, the old Wendigo homestead at Big Sand Point, that the scattered bones, already alluded to, are found, it seems strange that the story tellers do not represent them as the remains of the cannibal feasts of its former occupants. These evidences of mortality, however, are accounted for in another tradition, that tells of a war-party of Iroquois who, having taken possession of and entrenched or barricaded the old Wendigo mound, defended themselves to the death against a force of French and Indians, who surprised them in a night-attack and butchered them to a man.

This story seems to carry us back to that period of conflict which was inaugurated by the onslaught of the Iroquois upon the Huron towns, which was continued with unparalled ferocity and terminated only by the merciless destruction of a once powerful nation and the final dispersion of its fugitive remnants, together with such bands of Algonkins as happened to come within the scope of that campaign of extermination. It is supposed that our tradition has reference to one of the many scenes of bloodshed which reddened the frontiers of Canada, while the Confederates were thus making elbow-room for themselves on this continent, and were putting the finishing touches on the tribes to the north of the Great Lakes and the St.Lawrence. At this time all the carrying-places, on our great highway, were dangerous, for war-parties of the fierce invaders held the savage passes of the Ottawa, hovering like malignant okies amidst the spray of wild cataracts and foaming torrents, where they levied toll with the tomahawk and harvested with the scalping-knife the fatal souvenirs of conquest.

Sand Bay, at the outlet of Constance Creek, in the township of Torbolton, Carleton Co., Ont., is a deep indentation of the southern shore line of the Ottawa, extending inland about a mile. The entrance, or river front of the bay, is terminated on the west by Big Sand Point, and on the east by Pointe à la Bataille, the two points being about a mile apart. The latter is now shown on the maps as Lapotties Point, a name of recent origin and doubtless conferred upon it by some ox-witted yokel, it should bear the name of its latest occupant, which probably commemorated some tragic incident of a bygone age. The French Canadian river-men,

page 66

page 67

however, with much better taste, still retain the name by which it was known to the old voyageurs.

A great many years ago, so the story goes, a party of French fur-traders, together with a number of friendly Indians, possibly Algonkin and Huron allies, went into camp one evening at Pointe à la Bataille. Fires were lighted, kettles were slung and all preparations made to pass the night in peace and quietness. Soon, however, the lights from other camp fires began to glimmer through the foliage on the opposite shore of the bay, and a reconnaisance presently revealed a large war-party of Iroquois in a barricaded encampment on the Wendigo Mound at Big Sand Point. Well skilled as they were in all the artifices of forest warfare, the French and their Indian companions were satisfied that something would happen before morning. It was inevitable that the coming night would be crowded with such stirring incidents as would leave nothing to be desired, in the way of excitement. There lay the Iroquois camp, with its fierce denizens crouched like wolves in their lair, though buried in the heart of the enemy's country, yet self-reliant in the pride of warlike achievements, whose military strategy had rendered them invulnerable as the gloom of the oncoming thundercloud, and as inexorable as the fate of the forest monarch that is blasted by a stroke of its lightning.

Now the golden rule on the Indian frontier in those strenuous times, was to deal with your neighbor as you might be pretty sure he would deal with you, if he got the chance. Of course it was customary, among the Indians to heap coals of fire on the head of an enemy, but as it was the usual practice, before putting on the coals, to bind the enemy to some unmovable object, such as a tree or a stout picket, so that he was unable to shake them off, the custom was not productive of much brotherly love. Moreover, when the success of peace overtures could be assured only to the party that could bring the greater number of muskets into the negotiations, it will be readily understood why the French, who were in the minority, did not enter into diplomatic relations with the enemy. On the contrary, it was resolved to fight as soon as the opposing camp was in repose, and attempt a decisive blow from a quarter whence it would be least expected, thus forestalling an attack upon themselves, which might come at anytime before the dawn. The French and their allies knew very well that if their plans miscarried and the attack failed, the penalty would be death to most of their party, and that, in the event of capture, they would receive as fiery and painful an introduction to the world of shadows as the leisure or limited means of their captors might warrant.

Towards midnight, the attacking party left Pointe à la Bataille and

page 67

page 68

proceeded stealthily southward, in their canoes along the eastern rim of Sand Bay, crossed the outlet of Constance Creek and landing on the western shore of the bay advanced towards Big Sand Point through the pine forest that clothed, as it does to-day, the intervening sand hills. This long detour, of about two miles, was no doubt a necessity, as, on still nights, the most trifling sounds, especially such as might have been produced by paddles accidently touching the sides of canoes, are echoed to considerable distances in this locality.

The advance of the expedition was the development of Indian strategy, for, by getting behind the enemy, it enabled the French and their allies to rush his barricades and strike him in the back, while his sentinels and outliers were guarding against any danger that might approach from the river front.

The attack was entirely successful, for it descended upon and enveloped the sleeping camp like a hideous nightmare. Many of the Iroquois died in their sleep, while the rest of the party perished to a man, in the wild confusion of a midnight massacre.

Such is the popular tradition of the great fight at the Wendigo Mound at Big Sand Point, and the bones that are found in the drifting sands at that place, are said to be the remains of friend and foe who fell in that isolated and unrecorded struggle.

Let us now descend the river, as far as the Chaudière, and we find ourselves once again in the moccasin prints of the Iroquois; for those tirelss scalp hunters were quite at home on the Ottawa, as well as on its northern tributaries. War expeditions of the Confederates frequently combined business with recreation. They would leave their homes on the Mohawk or adjacent lakes and strike the trail to Canada by way of the Rideau Valley, hunt along that route until the spring thaws set in, and manage to reach the Ottawa in time for the opening of navigation. Then they loitered about the passes of the Chaudière and waited, like Wilkins Macawber, for something to turn up.

While waiting thus for their prey to break cover, from up or down the river, they devoted their spare time to various occupations. To the oki, whose thunderous voice was heard in the roar of the falls, they made sacrifices of tobacco; while the Mohawks and Onondagas each gave a name to that cauldron of seething water which is known to us as The Big Kettle. The Mohawks called it Tsitkanajoh, or the Floating Kettle, while the Onondagas named it Katsidagweh niyoh or Chief Council Fire. It is possible that our Big Kettle may be a modified or corrupted translation of the Mohawk term.

(To be continued ).

page 68

page 92

(Continued from page 68)

Iroquois tradition assigns to Squaw Bay, called also Cache Bay, at Tetreauville, the reputation of having been one of the favorite lurking places of these war-parties. It must have been in those days, an ideal spot for an ambush or concealed camp, as it occupied, for the purposes of river piracy, as unique a position on the old trade route, as does one of our present day toll-gates, for controlling the traffic on a turnpike road. There is no doubt of the place having been used as an Indian camping ground, at least in prehistoric times, as the shores of the bay are littered in, all directions with fragments and flakes of worked flint. This is an instance in which tradition is corroborated, to some extent, by archaeology.

It is also said that Brigham's Creek, called also Brewery Creek, a narrow channel of the Ottawa, was the old Indian portage route for overcoming the rapids of the Chaudière. It may be seen by glancing at a map of the city of Hull, that parties of Algonkins or Hurons, as the case may have been, upon emerging on the main river at the head of this portage, were liable at any time to receive a warm welcome from some surprise-party of Iroquois visitors at the Squaw Bay camping ground. If descending the rapids of the Little Chaudière, they faced a far worse predicament, as, unable to escape or defend themselves in the swift current, they would have been caught, like passing flies that are blown into a spider's web.

It is said that Indian cunning was at length successful in evolving a plan to outwit the military strategy of the Iroquois. As the old portage route had become dangerous it was resolved to have an alternative one. In ascending the Ottawa, this new portage started from the western shore of Brigham's Creek at a point now occupied by the International Cement Works. It continued thence in a westerly direction, skirting the foot of the mountain and passed down Breckenridge's Creek to the outlet of that stream into Lake Deschênes. It was rather a long portage of about a dozen miles, but the Algonkin and Huron had learned in the school of bitter experience, that, in their case, the longest way round was the shortest way home. An aged squaw, who many years ago, spoke of a similar forest trail that extended, in the early days, from a point on the Gatineau

page 92

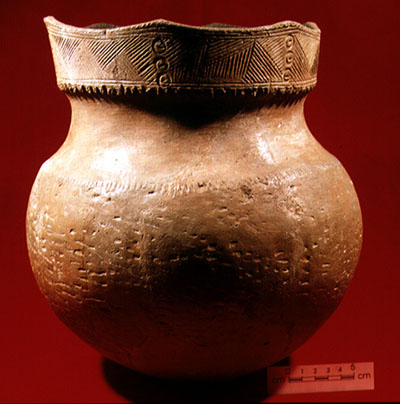

This figure represents a clay vessel, which was found by Mr. James Lusk, on his farm, Lot 20, Range XI, Township of Eardley, Wright Co., Que. It was purchased from Mr. Lusk in the year 1903, and is now in the Archaeological Section of the Geological Museum at Ottawa, where it is indexed as No. 3282A. The vessel is 11 inches in height and 33 inches in circumference.

(photo récente par Jean-Luc Pilon, Musée canadien des civilisations;

l'illustration originale dans la publication est sur une page sans numéro entre les pages 92 et 93)

page 93

near the site of Chelsea, thence by way of Kingsmere to a point on Lake Deschênes, now occupied by the town of Aylmer.

Reference has already been made to Indian camping grounds, which dot the shores of the Ottawa at frequent intervals. Let us see what can be made out of them, by a close examination of the relics they have yielded. The writer is convinced that these camp sites are of Algonkin origin, and that they bear evidences of casual contact, if not of more prolonged social intercourse with the Hurons. That is to say, that it looks as if the Hurons had been friendly visitors, who had spent much of their time in these Algonkin camps. These camp sites seem to have been selected with a view to observation, defence or escape in cases of sudden attack. The Hurons built their villages at some distance from the water highways, so as to escape observation by inquisitive tourists, who might wish to attack them. They also selected their village sites where the land, within a convenient distance, was suitable for agriculture. The highways of communication used by these village communities, were the innumerable forest trails, which traversed the Huron country in all directions. On the other hand, the Algonkins of the Ottawa have left traces of their camps along the edges of the river, on points of land which afford a good view up or down stream. They have been called canoe Indians and were at home on the water. As they were much more expert in the management of their birchen vessels than the Iroquoian races, they were in a position, on

the shores of the river, to escape by water from a too powerful enemy approaching by land, or they could retire to the forest if an overwhelming fleet appeared in the offing.

These camp sites are strewn with fragments of blackish flint, evidently procured from the Trenton limestone at the Chaudière, where it is found in great abundance, especially along Brigham's Creek, the old Indian portage route. Arrow-heads, fabricated from these fragments, are also found on these Algonkin camp sites. But there is also found an arrow-head of a different pattern, that is made from flint that has a lighter color and a broader and cleaner conchoidal fracture than the Algonkin forms. These arrow-heads bear a striking resemblance, in every respect, to those from the Huron country in western Ontario and there are no flakings of this latter flint to show that they were fabricated in these Algonkin workshops. This seems to be negative evidence that they were not made on the Ottawa, but may have been brought there by Huron visitors. It is not, of course, conclusive evidence of Huron occupation, but rather of Huron contact, more or less prolonged. A long knife of Huronian

page 93

page 94

slate, discovered on the Ottawa, by George Burland, with a broken gorget and a crescent shaped woman's knife, each of Huronian slate, found on the Bonnechere by Edward Moore, of Douglas, Ont., seem to be additional evidence of the presence of Hurons in the Ottawa Valley.

There are two other camp sites, however, that differ essentially from the foregoing and are without doubt distinctly Huron. The former of these was discovered by R. H. Haycock, of Ottawa, and the latter by Dr. H. M. Ami, of the Geological Survey.

In the fall of 1859 and the spring of 1860, the late Edward Haycock built a residence in the city of Hull, on the point now occupied by Gilmour's Mill. While making excavations for the foundation of a summer house, the workmen laid bare several ash-beds, at a depth of from two to three feet below the surface. Among other things, these beds contained fragments of Indian pottery in great abundance1. Mr. R. H. Haycock examined them closely and reports them as having been of a dark brown color, decorated with incised lines, notches and indentations. According to Mr. Haycock's description, this pottery, both in composition and decoration, was similar to that unearthed from old ash-beds in the Huron country, in Ontario.

One may observe, on approaching Hull by the Alexandra bridge, an extensive cut bank of sand and gravel, between the E. B. Eddy Co.'s sulphide Mill and the end of the bridge, and between Laurier Ave., and the river. This is the place from which the late Edward Haycock procured sand for building purposes on the Eastern and Western Blocks of the Departmental buildings, at Ottawa. During the excavation of this bank, a great many Indian relics were discovered, such as womens' knives, arrow-heads, tomahawks and pottery, but no description of this pottery is, obtainable. Here, according to white and red tradition, many bloody encounters took place between parties ascending or descending the river.

In the archaeological department of the Geological Museum at Ottawa, there is a large array of pottery fragments collected by Dr. H. M. Ami, some years ago, from an old ash-bed at Casselman, Ont. In the same cases, are specimens of Huron pottery from village sites in western Ontario, and, in comparing the two collections one is quite satisfied that both are products

1 "In some places rude pottery is found at a considerable depth, from different causes. In fire-places this may come from the practice of placing the fire in excavations in the ground", Earthenware of the New York Aborigines. William M. Beauchamp, Bulletin, New York State Museum, Vol. 5. No. 22, p. 80.

page 94

page 95

of the same school of ceramic art. The ash-bed was large and deep and Dr. Ami is of the opinion that it had been used as a fire-place for a considerable length of time. There is no doubt that Dr. Ami's discovery is of the highest importance in establishing proofs of Huron occupation of the Ottawa valley.

There are, also, in the Museum, two perfect specimens of Indian pottery from lot 20, range 11, Eardley township, Wright Co., Que. They were procured from James Lusk, who discovered them on his farm, where they had been washed out of the banks of a small creek during a freshet. They are superb examples of aboriginal art, and it is difficult to understand how they could have been brought to such symmetrical proportions without the use of a lathe. Compared with similar vessels figured in the Ontario Archaeological Reports, it seems impossible to doubt that they are of Huron origin. These vessels are similar in pattern and have been fabricated from the same clayey composition, with the same band, decorated with characteristic incised lines, about the top, and a wavelike edge on the summit of the rim, as are found in some of the Huron forms. As to whether the spot where this pottery was found is an ancient village site, will be an interesting subject for future investigation.

Let us now consider another phase of the question of Huron occupation, that seems to be more conclusive even than the discovery of ash-beds or pottery, the evidences of ossuarial burial. The graves of a nation are indexes of its intellectual development, from the rude cairn of the wandering savage to the Taj Mahal of the imperial ruler. Could we have mingled in the activities of palaeocosmic man, and witnessed the riteof sepulture by which the Old Man of Cro-Magnon was laid to rest in his cave-sepulchre on the Vezére, in the Dordogne Valley, then, the last rites about the grave of that post-glacial patriarch might have yielded us a store of knowledge that would have been invaluable to us in studying the savage culture of ancient Europe, such as the rude efforts of primitive man to interpret natural phenomena or to recognize in the variant manifestations of natural forces the evidences of divine anger or approbation. So, also, if we could have witnessed the burial rites of the Huron nation, in what was called the Feast of the Dead, they would have proved most instructive. They might have cleared up much that is obscure in regard to the ultimate destiny and relationship of the two souls, the one that took flight to the land of spirits, at the hour of death, and the other that awaited the final interment, before taking its departure. They might have given us an insight into the philosoihy of Indian burials, which would have explained the

presence or absence of warlike or domestic implements in Huron ossuaries. But, fortunately for

page 95

page 96

archaeology, the Jesuits and other contemporary writers have told us much that is invaluable concerning this important festival.

Reverence for their dead was a marked characteristic of the Huron people, a sentiment that was common among all the red races. It is doubtful if those refinements of Christian feeling that find expression in the mortuary rites of our civilized white races, are one whit more profound than those outpourings of sorrow, which were lavished by the Hurons upon the remains of their departed relatives, at their periodical Feasts of the Dead.

When the early settlers, in western Ontario, were clearing up their lands, they were frequently puzzled at the discovery of large pits filled with human bones, together with warlike and domestic implements and articles of personal adornment, all crowded together in these communal sepulchres. These bone-pits or ossuaries were at first attributed to burials for the disposal of the slain, after great battles, or of those who had perished during epidemics of disease. Their true origin, however, was established beyond conjecture by the Jesuit Relations.

Parkman, in the Jesuits in North America, has given us graphic details of what the Hurons considered their most solemn and important ceremonial. It was witnessed by Brébeuf at Ossossané, in the summer of 1636, and a report of it embodied in his Relation of the same year. The following brief description of the solemnity, compiled from the works of these writers, may answer our purpose, without going into details.

Every ten years, or so, each of the four nations of the Huron confederacy held a Feast of the Dead. The time and place, at which the feast should be held, was decided by the chiefs of the nation, in solemn council. All preliminary arrangements having been made, the dead of the past decade were collected from far and near and conveyed to the common rendezvous. Previously however, the corpses which had, as usual, been placed on scaffolds or, more rarely, in the earth, for the time being, were removed from their temporary resting places and prepared by loving relatives for the final rite of sepulture. The bones of such as were reduced to skeletons were tied up in bundles like faggots, wrapped in skins and clothed with pendant robes of costly furs. The bodies of the more recent dead were allowed to remain entire and were clothed also in furs. Then these ghastly bundles of mortality were hung on the cross-poles, which later on sustained the corn harvest, of the principal long-house in the village, and, while the mourners partook of a funeral feast, the chiefs discoursed upon the public or domestic virtues of the deceased. Then commenced the wierd funeral march along the woodland paths

page 96

page 97

through the gloomy pine forests of old Huronia, the mourners uttering, at intervals, dismal wailing cries, supposed to resemble those of disembodied spirits wending their way to the land of souls, and thought to have a soothing effect on the consciousness still residing in the bundles of bones, which each man carried.

The Jesuits had been invited, by the chiefs of the Nation of the Bear, to come to Ossossané and witness the rite. This great town of the Hurons lay some distance back from the eastern margin of Nottawassaga Bay, in the midst of a pine forest. What a sight it must have been to those Europeans, as, one after another, the weird funeral corteges, converging from the various towns of the Bear, issued from the surrounding forest.

During the delay, in awaiting the complete assemblage of the nation's dead, the squaws ladled out food for the inevitable feast, while the younger members of both sexes contended for prizes, donated by mourners in honor of departed relatives. So great was the assemblage that the houses were crowded to suffocation and large numbers had to camp out, in the adjacent forest. The bundles of dead were hung from the cross-poles in the houses, and in the one where the Jesuits were housed upwards of one hundred packages of mortality decorated the interior of the building. The Jesuits passed the night in one of these places, and endured the ordeal with Christian fortitude.

Finally, the signal was given, by the chiefs, for the consummation of the concluding rite. The packages of dead were opened and tears and lamentations lavished upon their contents. Brébeuf refers to one woman in particular, whose ecstasies of grief, over the bones of her father and children, were pathetic in the extreme. She combed her father's hair, and fondled his bones as if they had been alive. She made bracelets of beads for the arms of her children, and bathed their bones with her tears. It was the same divine light of motherhood, which thus irradiated the savage dens of the Hurons, as that which shines in the eyes of the Christian mother, as she weeps over the cold form of one whose brows have been sealed with the sign of the Cross.

The.various processions now re-formed and proceeded to a spot in the forest, where a clearing of several acres had been made. In the centre of this open space a huge pit had been dug, ten feet in depth and thirty feet in diameter. Around this pit a rude scaffold had been erected, very high and strong. Above this scaffold rose a number of upright poles with others crossed between, upon which to hang the funeral gifts and remains of the dead.

The different groups of mourners were assigned places around the edge of the clearing. The funeral gifts were now

page 97

page 98

displayed, among them being many robes of the richest fur that had been prepared, years before, in anticipation of this ceremony. The kettles were then slung and feasting went on until the middle of the afternoon, when the bundles of bones were again taken up. Then, at a signal from the chiefs, the crowd rushed forward from all sides, like warriors at the storming of a palisaded town, climbed, by means of rude ladders, to the scaffolding and hung their dead, together with the funeral gifts, to the cross-poles. Then they retired and the chiefs, from the scaffolding, made speeches to the people, praising the dead and extolling the gifts given in their honor.

During this speech making, the vast grave was being lined throughout with robes of beaver skin, with three copper kettles in the centre. The bodies, which had been left whole, were then cast into the pit amidst great confusion and excitement, and, as darkness was now coming on, the ceremony was adjourned until the next day, the assemblage remaining about the great watch-fires, which blazed about the edge of the clearing.

Just before daylight, the Jesuits, who had retired to the village, were aroused by an uproar fit to wake the dead. Guided by the noise, they hastened back to the clearing where they beheld a spectacle that surpassed anything they had ever witnessed. Brébeuf says that nothing had ever figured to him better the confusion among the damned. One of the bundles of bones had fallen from the poles into the pit and precipitated the conclusion of the rite. Huge fires which blazed about the clearing lit up a fearful scene. On and about the scaffold, wild forms, howling like demons, hurled the packages of bones into the pit, where a number of others moved about amidst the ghastly shower and with long poles arranged the bones in their places. Then the pit was covered with logs and earth and the ceremony concluded with a funeral chant that resembled the wail of a legion of lost spirits. It was the death song of a lost people, the knell of a passing race.

One can imagine, as a spectator of this weird scene, the stalwart form of Brébeuf, towering in the majesty of his fore-doomed martyrdom, and gloriou in the might of that indomitable courage that triumphed, in the hour of his death, over the ingenuity of his tormentors, evolving in his mind such subtle arguments as might subordinate to higher ideals the rude Natureworship of Huronian.clanship, and win to the service of his Master these hordes of heathendom.

Residents of the Capital will be surprised to learn, that a Huron Feast of the Dead, similar to the one already described, was once held in Ottawa, on the spot that now occupies the north-west angle formed by the intersection of Wellington and

page 98

page 99

Bay Streets. This is no fiction, but a fact, supported by the most trustworthy evidence. The proof is contained in an article in the Canadian Journal, Vol. 1, 1852-1853, by the late Dr. Edward Van Courtland, which describes an Indian burying ground and its contents discovered at Bytown (Ottawa) in 1843.

Dr. Van Courtland states that in 1843 some workmen, who were digging sand for mortar for the old suspension bridge, unearthed a large quantity of human bones. He immediately hurried to the spot and found that the contents of an Indian burying ground were being uncovered. The doctor continues: "Nothing possibly could have been more happily chosen for sepulture than the spot in question, situated on a projecting point of land directly in rear of the encampment, at a carrying place and about half a mile below the mighty cataract of the Chaudière, it at once demonstrated a fact handed down to us by tradition, that the aborigines were in the habit when they could, of burving their dead near running waters. The very oldest settlers, including the Patriarch of the Ottawa, the late Philemon Wright, and who had located nearby some thirty years before2 had never heard of this being a burying place, although Indians existed in considerable numbers about the locality when he dwelt in the forest, added to the fact that a huge pine tree growing directly over one of the graves, was conclusive evidence of its being used as a place of sepulture long ere the white man in his progressive march had desolated the hearths of the untutored savage." After two days digging the results were as follows:

"One very large, apparently common grave, containing the vestiges of about twenty bodies, of various ages, a goodly share of them being children, together with portions of the remains of two dogs heads; the confused state in which the bones were found showed that no care whatever had been taken in burying the original owners, and a question presented itself as to whether they might not have all been thrown indiscriminately into one pit at the same time, having fallen victims to some epidemic, or beneath the hands of some other hostile tribe; nothing however, could be detected on the skulls, to indicate that they fell by the tomahawk, but save sundry long bones, a few pelvi, and six perfect skulls the remainder crumbled into dust on exposure to the air, in every instance the bones were deeply colored from Red Hematite which the aborigines used in painting, or rather in bedaubing their bodies, falling in the form of a deposit on them when the flesh had become corrupted. The material appears to have been very lavishly applied from the fact of the sand

2 Philemon Wright, with 25 followers, arrived at the site of the present City of Hull on the 7th of March, 1800.

page 99

page 100

which filled the crania being entirely colored by it. A few implements and weapons of the very rudest description were discovered, to wit:- 1st, a piece of gneiss about two feet long, tapering, and evidently intended as a sort of war-club; it is in size and shape not unlike a policeman's staff. 2nd, a stone gouge, very rudely constructed of fossiliferous limestone; it is about ten inches long, and contains a fossil leptina on one of its edges; it is used, I lately learned from an Indian chief, for skinning the beaver. 3rd, a stone hatchet of the same material. 4th, a sandstone boulder weighing about four pounds; it was found lying on the sternum of a chief of gigantic stature, who was buried apart from the others, and who had been walled round with great care. The boulder in question is completely circular and much in the shape of a large ship biscuit before it is stamped or placed in the oven, its use was, after being sewed in a skin bag, to serve as a corselet and protect the wearer against the arrows of an adversary. In every instance the teeth were perfect and not one unsound one was to be detected, at the same time they were all well worn down by trituration, it being a well known fact that in Council the Indians are in the habit of using their lower-jaw like a ruminating animal, which fully accounts for the pecularity. There were no arrowheads or other weapons discovered."

It will be seen, from the foregoing, that the worthy doctor had unearthed a small Huron ossuary, similar in its general features to the much larger one at Ossossané, and if the doctor's description is compared with reports on communal graves, in western Ontario, by such eminent archaeologists as Dr. David Boyle, curator of the Provincial Museum at Toronto, A.F.Hunter, George E. Laidlaw and others, one must be convinced that the Wellington Street ossuary was of Huron origin. When the doctor raises the question as to whether the bodies had not all been "thrown incdiscriminately into one pit at the same time" he suggests a mode of sepulture that was actually observed by Brébeuf at the Huron Feast of the Dead at Ossossané.

Another small ossuary was uncovered some years ago, on Aylmer Island, when the foundation for the new lighthouse was being excavated. The writer was not present at the exhumation of its contents, but the light-keeper, Mr. Frank Boucher, informed him that the skeletons were all piled together, indiscriminately. It is difficult to estimate the number of bodies interred in this grave, but it yielded about a wagon load of bones. A number of single graves have also been found at this spot, and these, together, with the ossuary would seem to prove that Algonkin and Huron occupied this part of the Ottawa Valley and used this island in common as a place of sepulture.

page 100

page 101

Embowered in the solemn grandeur of a mighty forest of gloomy pine, old Lac Chaudière-our Lake Deschênes-was a fitting theatre for that weird ceremonial, the Huron Feast of the Dead. Resting on the old Algonkin camping ground at Pointe aux Pins-now the Queen's Park-some roving coureur de bois might have seen this great sheet of water fading away into the vast green ocean of foliage to the south, and witnessed from his point of vantage the uncanny incidents of the savage drama. From various points on the lake he might have seen, converging on the island, great war canoes, freighted with the living and the dead, the sad remnants of a passing race. He might have heard the long drawn out wailing cries of the living as they floated in unison across the water, outrivalling the call of the loon or the dismal and prolonged howl of the wolf, as they echoed through the arches of the forest, and as the island rose before his vision, tenanted with its grotesque assemblage of dusky forms, engaged in the final rite of sepulture, he might have mused upon the mutability of human life, in its application to the red denizens of the wilderness, whether in the dissolution of a clan, a tribe or a nation.

We have now reviewed three distinct sets of evidence, which verify one another and sustain, collectively, the hypothesis of Huron occupation of the Ottawa Valley. We have Huron arrowheads and slate implements on Algonkin camping grounds, we have Huron pottery from ash-beds that smouldered, possibly, in Huron long-houses, for considerable periods of time, and lastly, we have ossuaries or communal graves, a mode of sepulture characteristic of the Huron people, and one which would indicate a permanent and somewhat lengthened period of occupation.

Of course, it will be urged that no band of Hurons would have built a village so near the river as the site of the old ash-beds at Gilmour's Mill, in Hull, but, as the Algonkins lived, sometimes, in the Huron country and adopted, to some extent, the customs of their confederates, might not the Hurons, if, they came to live with the Algonkins on the Ottawa, have followed the usage of the latter in the selection of their dwelling places.

The evidence, so far obtained, seems to have given us fairly conclusive proofs of Huron occupation of the Ottawa Valley, and the beginning of a new chapter in the history of one of the great native races of Canada, but, as yet, we have no data that gives us aclue to the time of this period of occupation. Our two ossuaries, already referred to, yielded nothing that could be traced to the white trader; yet, this is not negative evidence that the interments were made before European contact. The Wellington Street ossuary held quite a number of implements, while that on Aylmer Island had none. As Dr. David Boyle remarks: "The

page 101

page 102

truth is we are yet in the dark regarding the philosophy of aboriginal burials, and, perhaps will ever remain so." So that in the absence of evidence we can indulge only in conjecture.

It will be remembered that, after the four nations of the Huron Confederacy went down in red ruin beneath the merciless tomahawks of the Iroquois, the conquerors turned their victorious arms against the Neutrals or Attiwanderons; stormed and took their palisaded towns, together with hundreds of prisoners, whom they burnt or adopted, and left a trail of fire and blood along the northern shores of Lake Erie. Then they wheeled in their tracks and rushed, like a pack of famished wolves, upon the Eries or Cats, a kindred tribe to the south of Lake Erie, whom they destroyed utterly in one of the fiercest Indian battles recorded in history. Meanwhile, on the eastern frontiers of the Iroquois Confederacy, the Mohawks were at war with their Algonkin neighbors, the Mohicans, and with their own Iroquoian kinsmen, the Andastes or Conestogas. During a decade of conflict with these opposing forces, a series of bloody reverses had humbled the Mohawk arrogance, when the other four nations of the Iroquois league took up the strife, in the Andaste war. For fifteen years the Iroquois' war-parties traversed the forests towards the Susquehanna before the heroic Andastes were wasted away by the attrition of superior numbers and finally overcome by the Senecas, about the year 1675. Thus, in a period of twenty-five years, from the downfall of the Hurons to the conquest of the Andastes, the Iroquois had triumphed over all the neighboring nations and peace reigned, for a

time, over the blood stained wilderness. But, during all these wars, the Confederates were able to send war-parties on the trail to Canada, that kept New France in a turmoil, by cutting off her outposts and wasting her outlying settlements. It is not likely, however, that any of these expeditions went out of their way to attack Algonkin or Huron stragglers on the Ottawa, and these fugitive bands may have remained unmolested for a few years, until their final destruction or dispersion could be made an incident in some more important enterprise of the Iroquois.

Let us now return to the Hurons. In the year 1650, after a terrible winter made horrible by famine, death and the Iroquois, the Jesuits abandoned their last mission fort of Ste. Marie on Ahoendoé-St. Joseph's or Christian Island-and led some three hundred of these unfortunate people to Quebec, by way of the Ottawa. A much larger number however, who were left behind, were forced by the Iroquois to abandon their fort and retire to Manitoulin Island and the northern forests. But the Iroquois were on their trail; so, finally, loading their canoes, about four

page 102

page 103

hundred of them took the route of the Ottawa to join their kindred who had preceded them. Other scattered bands followed, from time to time, of which we appear to have no definite record. By this time the whole Ottawa River had been swept by the tornado of Iroquois ferocity and its shores had become a solitude.

Now for our conjecture. Cases are not infrequent in which Indian communities have been forced to abandon their homes, through stress of war, but have again returned to them after some years, when the war cloud had given place to the sunlight of peace. Doubtless, in their wanderings on the northern tributaries of the Ottawa, Algonkin and Huron had alike eaten the bread of adversity and drunk the water of affliction and were ready for any asylum that would afford them a brief period of rest. Now, while the time of the Iroquois was fully occupied in the terrible wars already enumerated, may it not have been possible that some of the fugitive remnants of the Hurons, on their way to Quebec, stopped and settled on the Ottawa, together with similar bands of Algonkins, who had returned to their old camping grounds?

A serious objection, of course, to the theory of Huron occupation of the Ottawa Valley, in the latter half of the seventeenth century, is the presence of Huron pottery in the ash-beds at Hull and Casselman, as the Indians are supposed to have discarded their native earthenware for the brass or copper kettles of the white trader, soon after the advent of Europeans, still, however, it should be borne in mind that the craggan, (see Annual Archaeological Report 1906 (Toronto 1907) pp. 16-18), an earthen vessel of domestic manufacture, made from unrefined clay and similar in design and finish to the very crudest forms of our Indian pottery, was made and used until quite recently-if it is not used, even, to-day-in the kitchens of several of the Scottish Islands, and that these vessels were preferred, for many purposes, to the more costly and highly finished products of modern ceramic art. These craggans were made by housewives to serve, among others, the purposes of drinking vessels and pots for boiling; so that if such prehistoric pottery could have survived among the Scottish Islanders, to a time within the memory of the living in competition with domestic innovations of centuries of civilization, why should not the Hurons of the Ottawa have retained, for a few years at least, the earthenware of their ancestors, under somewhat similar conditions? Finally, William M. Beauchamp3 refers to a

3 Earthenware of the New York Aborigines. Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Vol. 5, No. 22, October, 1898, p 80.

page 103

page 104

similar survival of the use of pottery, among the Iroquois, as follows: "Refuse heaps, by village sites, usually contain a great deal of earthenware, out of which fine or curious fragments are often taken, and these occur also in the ash beds of the old fireplaces. This is so on some quite recent sites, for while the richer Iroquois obtained brass kettles quickly from the whites, their poorer friends continued the primitive art till the beginning, of the 18th century at least." Another statement by the same writer, is important, as it would exclude the probability of our pottery being referable to the Algonkins. He writes, in the Bulletin referred to, at page 76, as follows: "In fact, the Canadian Indians do not appear to have used earthenware in early days, with the exception of the allied Hurons and Petuns, the Neutrals and the Iroquois of the St. Lawrence, all of these being of one family.....The nomadic tribes, however, preferred vessels of bark, easily carried but not easily broken. In these they heated water with hot stones, as the Iroquois may sometimes have done."

The above theory, as to the time of Huron occupation, is only a suggestion, unsupported at present by sufficient evidence to prove it. It may turn out, eventually, that the fireplaces of this vanished race grew cold, on the Ottawa, in the dim twilight of a more remote antiquity. Is it possible that, before the coming of the white man, the old Wyandots or Tionnontates, in the course of their traditionary wanderings, so admirably described bv William E. Connelley, may have remained for a time on the Ottawa, and left us only their ashbeds and ossuaries to puzzle over?

Another question also suggests itself. Where did the Hurons go to after leaving the Ottawa? They appear and disappear on the stage of tribal activities, either standing boldly forth in some historic incident, or dimly silhouetted by the light of tradition, on the dark back-ground of prehistoric time. Did they migrate, finally, to join their kindred in their distant resting places? Did they fade away, by adoption, into other tribes? Or,were they absorbed bv the red cloud of massacre, to disappear forever in the darksome shadow of the illimitable wilderness?

|