| |

|

|

| |

Dupuis

Frères, Spring/Summer Catalogue, 1934, p. 2. Dupuis

Frères, Spring/Summer Catalogue, 1934, p. 2.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Read the Fine Print: How the Postal Service Served the

Mail-order

Industry

by Gaëtanne

Blais

The Post Office serviced the mail-order industry in

many ways:

by shipping catalogues and merchandise and offering various fee schedules;

by

issuing money orders and postal notes so that customers could pay for

their merchandise

by mail; and, by collecting money on cash-on-delivery orders. The

mail-order

houses responded and adapted in their own ways.

Introduction | How the

Mail-order

Business Fit with the Postal Service | Paying for the

Order

| Shipping the Merchandise | Free

Shipping

| Using Local Postage Rates | Shipping

Perishables

| Returning Merchandise | Conclusion

|

Further Reading

Introduction

The Canadian Postal Museum (CPM) has collected various objects related

to

the sale of merchandise by mail, including mail-order catalogues, order

forms,

envelopes for sending order forms, samples, postal notes, and money

orders. Such

objects are significant as they illustrate the importance of the postal

service

in making a wide variety of merchandise available to all Canadians,

especially

in rural areas. Through an examination of documents from the collection

dating

back to the 1930s, a view of the relationship between the Post Office

department

and mail-order houses emerges. The Post Office department earned revenue

from

mail-order houses; mail-order houses sold a wide variety of goods, and

customers

had access to goods not available locally. Everyone benefited. Yet, there

is

evidence of tension.

How the Mail-order Business Fit with the Postal

Service

Mailing to the Customers

Mail-order catalogues and merchandise fell into two mail matter

categories: third-class

mail and parcel post. Third-class mail included newspapers and periodicals

as

well as books, pamphlets, circulars, and catalogues. Thus, catalogues and

samples

could be mailed at lower rates.

| |

|

|

| |

Army

and Navy Expansion Sale Catalogue, 1937, cover. Army

and Navy Expansion Sale Catalogue, 1937, cover.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The Post Office department facilitated the shipment of catalogues

through

arrangements "whereby the prepayment of postage on such matter may

be effected

in cash (instead of by postage stamps) … Each article must have

printed

upon its wrapper or cover an impression of one of the official stamps

provided

for the purpose." A permit and an electrotype

("electro") bearing

the name of the post office, the permit number, and the amount of prepaid

postage

had to be obtained from the postmaster. Such arrangements could only be

made

at larger post offices in cities where mail-order houses were established

and

"where there is a system of checking and accounting which fully

protects

the postal revenue."

|

|

The shipment of samples was described in a category of its own. The

Canadian

Postal Museum's samples fit the Post Office department's

guidelines

in terms of size and weight limits and contents that were "not of

saleable

value." However, there is no mention in the guidelines for

or

against the use of the envelope as a marketing tool, which was

clearly

Eaton's intention. The graphics are attractive and the text goes

beyond

"such words as may be necessary to indicate precisely the origin and

nature

of the merchandise."

|

| |

|

|

| |

Packet

and samples, Eaton's Wallpaper Book, 1933. Packet

and samples, Eaton's Wallpaper Book, 1933.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Parcel Post was used for shipping "farm and factory products

…

dry goods, groceries, hardware, confectionery, stationery, … seeds,

cuttings,

bulbs, roots … and all other matter not included in the first class,

and

not excluded from the mails by the general prohibitory regulations with

respect

to objectionable matter." As mail-order houses shipped large numbers

of

parcels of varying weights and sizes, they had to inform themselves of the

numerous

parcel post regulations and rates (25 regulations described over 13 pages

in

the 1933 Official Postal Guide).

But, calculating the correct amount of postage to include could be

daunting

for the customer. What if a person did not want the

"buy-for-$5.00-and-we-pay-the-shipping-charges"

deal? Then, an "amount allowed for charges" had to be enclosed

with

the order. Or, when buying seeds from Eaton's, a customer had to

determine

which merchandise was "price delivered" (whereby Eaton's

paid

the delivery charges) and which was not. Could everything be ordered and

shipped

at once to save on charges? A chart of distances and weights was used to

determine

what was owed for shipping merchandise so that Eaton's could

determine

how much could be subtracted for their part of the charges.

Proximity to the Post Office or Railway

Some details on order forms and envelopes appear insignificant

until

they are examined in light of postal guidelines. To order wallpaper, for

example,

the customer had to include his or her name, the name of the closest post

office,

a street name, the rural route or post office box number, and the

province. A

customer's street address was insufficient.

A post office name was required by Eaton's and other mail-order

houses

to make sure the merchandise was delivered to the right person and to

establish

whether money-order service and train service were available. Thus, the

order

form in Eaton's wallpaper catalogue asks: "Is there an agent

at your

station? How many miles do you live from the station?"

Such factors were important especially when shipping fragile items:

"There

are certain post offices in Canada, situated on Railway Lines which are

served

by what is known as 'Catch Post Service' only, as the mail trains do not

stop

there. In these cases the mailbags are taken on and thrown off moving

trains,

and it has been found impossible to handle fragile parcels

satisfactorily."

Paying for the Order

| |

|

|

| |

Order-form

envelope, Eaton's Wallpaper Book, 1933. Order-form

envelope, Eaton's Wallpaper Book, 1933.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

When ordering from a mail-order house, customers could pay using money

orders

or postal notes. The amount could be sent with the order form or paid by

Cash

on Delivery (COD). Money orders and postal notes were highly recommended

by Dupuis

Frères as they were cheap and perfectly secure. Eaton's also

encouraged

these methods of payment and reminded its customers on the order form

envelope:

"Did You Enclose Money Order?"

|

| |

|

|

| |

Money

order. Money

order.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

To ensure the popularity of this service in the eyes of mail-order

companies

and consumers, these modes of payment had to be practical and secure.

Money orders

could be issued in amounts up to $100, the limit on a single money order.

Multiple

money orders of $100 could also be purchased. They were a safe way of

sending

money. In case of loss, a duplicate could be obtained.

| |

|

|

| |

Postal

note. Postal

note.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Whereas money orders were used for larger orders, postal notes were

used for

smaller ones, from 10 cents to $5. As with money orders, postal notes

could be

traced and duplicates issued. Eaton's further emphasized in its 1938

seed

catalogue that money orders and postal notes "prevent loss and

protect

all concerned."

| |

|

|

| |

Seed

order form, Eaton's Seeds Catalogue, 1938. Seed

order form, Eaton's Seeds Catalogue, 1938.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Money orders and postal notes facilitated the purchase of merchandise

by being

readily available to customers. In addition, there was money to be made by

the

Post Office department. In the fiscal year ending March 31, 1934, a total

of

11 790 068 money orders worth $101 926 368.91,

generated

gross revenues of $1 462 016.60. A total of 5 115 761 postal

notes

were issued worth $9 247 458.65 and generated revenues of

$114 308.02.

Shipping the Merchandise

Cash on Delivery (COD)

Once an order was prepared, the mail-order house could ship by

Cash

on Delivery (COD).The postmaster or mail contractor (if in a rural area)

was

responsible for collecting the payment from the customer and returning it

to

the mail-order company.

| |

|

|

| |

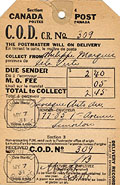

COD

tag, 1931. COD

tag, 1931.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Army

and Navy Bankers' and Manufacturers' Liquidation Sale Catalogue,

Fall/Winter

1932-33, p. 2. Army

and Navy Bankers' and Manufacturers' Liquidation Sale Catalogue,

Fall/Winter

1932-33, p. 2.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Army and Navy offered this service somewhat offhandedly, "We ship

COD

if you request this service," while Dupuis Frères did not

recommend

it because, they said, it was more costly for the customer and could cause

delays.

The Post Office department charged a commission for the service, which

was

passed on to the customer. In 1933-34, the COD fee schedule was as

follows:

"15 cents if the amount to be collected is not more than $50.00; 30

cents

if the amount to be collected is more than $50.00; limit of collection,

$100.00.

The fee must be paid by means of postage stamps affixed to the article by

the

sender [i.e., the mail-order house], and is additional to the ordinary

postage."

|

| |

|

|

| |

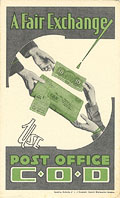

An

advertisement for Cash on Delivery. An

advertisement for Cash on Delivery.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Although not all post offices in Canada were "accounting"

or money-order

post offices, rural post offices were and thus could obtain COD service.

In 1933-34,

the Post Office department handled approximately 1 709 304 COD parcels

that generated

$256 395.60 in fees, an average of $6 per collection. These fees added up.

Oblivious

to the opinion of the mail-order houses, the Post Office department pushed

COD.

|

Free Shipping

As a further means of enticing customers, mail-order houses offered to

pay

shipping charges on orders of a certain amount, thus encouraging the

customer

to spend more, without necessarily increasing shipping charges for the

company:

"We pay shipping charges on all orders of $5.00 or over. If your

order

does not amount to $5.00 you can make it up to this amount with items from

our

General Catalogue."

Army and Navy offered to "pay postage or express charges on every

order

big or small." This incentive was repeated on every second page in

their

1932-33 catalogue, and was still available in 1937. In addition to

free

shipping charges, Army and Navy offered gifts on orders "ten dollars

or

more." Dupuis Frères made shipping a bit more complex.

Delivery

was paid on orders of $2 or $5, but only on certain items. Read the fine

print!

In its 1938 seed catalogue, Eaton's offered to pay delivery

charges

(although not on parcels shipped Air Mail or COD) on all the garden seeds

marked

"Price Delivered." This meant Eaton's paid for mail

delivery

to the nearest post office (thus the requirement for the name of the post

office

on the order form) or to the nearest railway station for larger orders.

Delivery

Charges were extra on "Field Seeds, Seed Potatoes, Rose Bushes,

Onion Sets,

Bulbs, Roots, Plants and Fertilizers." As these items were

perishable and

probably ordered in such quantities and weights to require special

treatment:

"Be sure to see your Station Agent regarding the Special Low Freight

Rate

on Farm Seeds."

Eaton's also shipped by airmail upon customer request, but would

only

pay the standard parcel postal rate on items for which it accepted to pay

delivery

charges. Customers had to: "Make inquiries from your postmaster as

to Air

Mail Rates, and be sure to enclose sufficient money to pay the extra Air

Mail

Charges." In all cases, Eaton's kept to its guideline:

"We

reserve the right to ship the cheapest way."

Using Local Postage Rates

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, tensions over postage costs grew

between

the Post Office department and the mail-order houses. To keep postage

costs down,

Eaton's and other mail-order houses shipped their parcels to

distribution

centres using their own fleets of trucks or express companies (transport

by truck

or train). Once at these centres, parcels were mailed to customers using

low,

local postage rates.

This was against Post Office department guidelines, as expressed in the

filed

correspondence: "Mail order houses have again made application to

ship

their parcels of merchandise part way by fast freight and then mail them

for

distribution at the lower parcel post rates … [W]e have always

compelled

mail order houses to mail their parcels of merchandise at the natural

office

of posting … paying the full parcel post rates covering transmission

by

post all the way. We have always taken the stand that to grant them the

special

concession which they ask … would be an infringement of the pledge

given

to country merchants when parcel post was inaugurated [in 1914]."

Very noble sentiments, indeed. In 1932, the Post Office department was

earning

"$3 500 000 per annum from mail-order houses for conveying

their

parcels by post."

Shipping Perishables

Although not a complaint against the post office or the railway

service,

Eaton's felt it was necessary to warn customers against shipping

perishables

at certain times of year: "Please note that we cannot ship Seed

Potatoes,

Onion Sets …during the cold weather on account of the danger of

freezing.

Orders received at a time when, in our opinion, it is unsafe to ship on

account

of frost, will be held, together with remittance (including postal

charges) until

is safe to ship."

Returning Merchandise

| |

|

|

| |

Instruction

sheet, Eaton's Wallpaper Book, 1933. Instruction

sheet, Eaton's Wallpaper Book, 1933.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

To avoid merchandise returns, Eaton's made sure its customers

understood

the merchandise. For example, in its 1933 wallpaper catalogue, detailed

instructions

were included. Nevertheless, Eaton's provided customers with a

"Goods

Satisfactory or Money Refunded" guarantee: "[I]f you are not

perfectly

satisfied, return what you have left and we will refund the money you paid

for

the entire lot, including shipping charges." (It's not in the

fine

print but the customer had to pay the cost of returning the goods.) When

an order

was delivered COD, customers were not permitted to examine the parcel

before

paying the charges, nor could they give back the parcel and request a

refund:

"[T]he COD service does not carry with it any examination privilege

…In

the event of the addressee having paid the charges due on a COD article,

and

after examination of the same desiring to hand the article back, and have

the

money refunded, such request is under no circumstances to be complied

with."

Conclusion

The documents examined here were produced by Eaton's, Army and

Navy,

and Dupuis Frères, and are a testimony to manoeuvring on the part

of both

the Post Office department and the mail-order houses. Although the

relationship

between two was not always amicable and had its inconveniences, it was

beneficial

to both partners.

Everything possible was done by the mail-order houses to ease the

shipping

process for their customers, at the lowest possible cost to themselves.

Not surprisingly,

subtle advertisements for free shipping and free gifts must have been

powerful

incentives during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

To shore up its relationship with the Post Office department,

mail-order houses

took out ads thanking the Post Office employees. One such ad celebrated,

unfettered,

the spirit of co-operation with which postmasters processed mail-order

merchandise.

Yet, other ads, while thanking postmasters for their good work, also

served as

reminders to the postal service of its responsibility to maintain a good

relationship.

The handling of catalogues was an incremental part of the mail-order

process.

Postmasters at the mailing end would receive large quantities of circulars

and

catalogues (bundles of 50, 75, and 100). These had to be counted and

weighed

and the postage checked. Postmasters at the receiving end had to comply

with

postal regulations and with the mail-order houses when items were

addressed "Householder,"

or had to be redirected or returned due to non-delivery, etc.

So, by quoting the Postal Guide in this last ad, the Robert Simpson

Company

Ltd. had a very effective argument, characteristic of this relationship

-

it required the Post Office department to read its own fine print!

Further Reading

Canada Official Postal Guide, 1933. Ottawa: Post Office

Department,

1933.

National Archives of Canada, RG13, Justice, Series A-2, Volume 368,

file 1932-740,

"Post Office Department - Proposed Evasion of Higher Parcel

Post

Rates by Mail Order Houses."

Report of the Postmaster General for the Year Ended 31 March

1934.

Ottawa: Post Office Department, 1934.

|